What are the first few things that come to your mind when you think of design? Chances are, you probably initially thought of: visuals, aesthetics, user interface, and making objects “look” good. And you’d be correct to infer that all of these aspects are very significant in the design world. I, for one, value the appearance of objects, especially given that I used to be a Graphic designer at a sign shop.

But let’s dig a little deeper.

Any kind of designer—be it a Graphic Designer, Product Designer, Web Designer, App Designer, you name it—is faced with a series of challenges, big or small, with any design project. Ninety-nine percent of the time, a designer does not simply try to execute a finished product from the get-go via raw talent plucked from their brain. An effective designer turns every design challenge into a process. Design is actually best used as an action verb, not a static noun. Obviously the final product is important (is that not the whole point?). But, the vast series of steps to reach that point is fundamental to its success.

In Jesse James Garrett’s book The Elements of User Experience (which I received as a Christmas present conveniently before my first ever UX course), Garrett describes the Design Process for the web via a series of planes, ranging from more abstract to more concrete:

Strategy -> Scope -> Structure -> Skeleton -> Surface

While some planes are more abstract than others, what all of them have in common is that they can all be externalized and mapped out into physical, visual ‘things’ that have the potential to thoroughly convey ideas and thought processes to colleagues and web developers in a team setting.

Now, let’s expand on this “planes” concept to approaches outside of the web.

Validating My Own View of the Design Process

Not to go too much on a tangent, but as someone with the inattentive form of ADHD, I have significant trouble organizing my brain and executing basic tasks in an orderly manner. However, a coping mechanism that I’ve learned even before I knew that I had the disorder was to translate my thoughts into the physical world. I try to repeatedly convince myself: “Have a thought or idea? No matter how stupid or radical it may be, write it down or create some visual representation of it, without judgement.”

The video below—which is almost a decade old but still holds value to me—has essentially validated my way of thinking and executing.

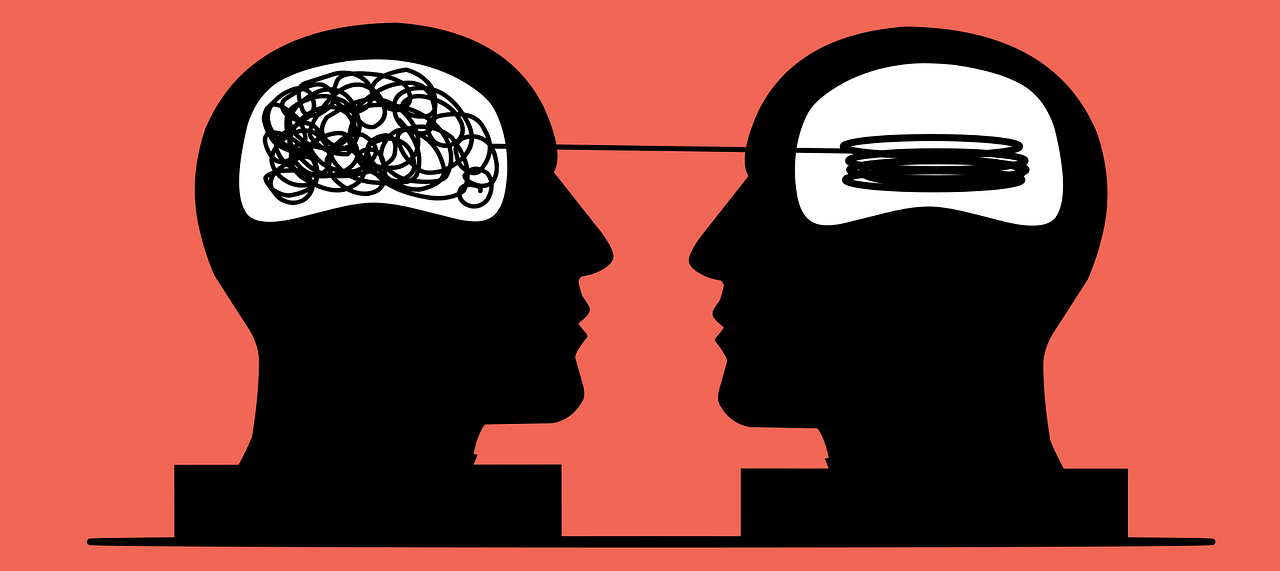

Here, psychologist Dr. Russell Barkley states that the key to organizing thoughts and executive functions for people with ADHD is to externalize everything, be it: charts, lists, tables, post-it notes, 3D objects, you name it. Essentially, bringing the incoherent thoughts and messy ideas into the physical world allows one to organize them, which significantly helps refuel the limited mental “fuel tank” that ADHD brains have. This way, I don’t overthink my brain into exhaustion before I even get started with a task.

So what does a seminar on ADHD have to do with the practicality of Design Thinking? Well, after some thought, I have come to the realization that Design Thinking—it being a process that is executed via a series of steps and translating thoughts into visuals—validates and refines the coping mechanisms for executive function that I, and many others alike, have already developed for inattentive ADHD. After all, everyone, ADHD and non-ADHD alike, gets to see one’s thoughts on display through a wide range of relatable visuals.

Final Thoughts

As explained, the whole design process is crucial for executing an effective, finished product, which consequently benefits both the business, the client, and the world.

Whichever structure or model you follow for Design Thinking, one important reminder is that they are fluid; they do not have to be rigid or followed religiously. You can always go back a step, skip ahead to another step, repeat a step again and again, or even combine steps if they seem redundant on their own. By being flexible, you are allowing yourself to be dynamic in our already dynamic world—and that has the potential to show in the final product.